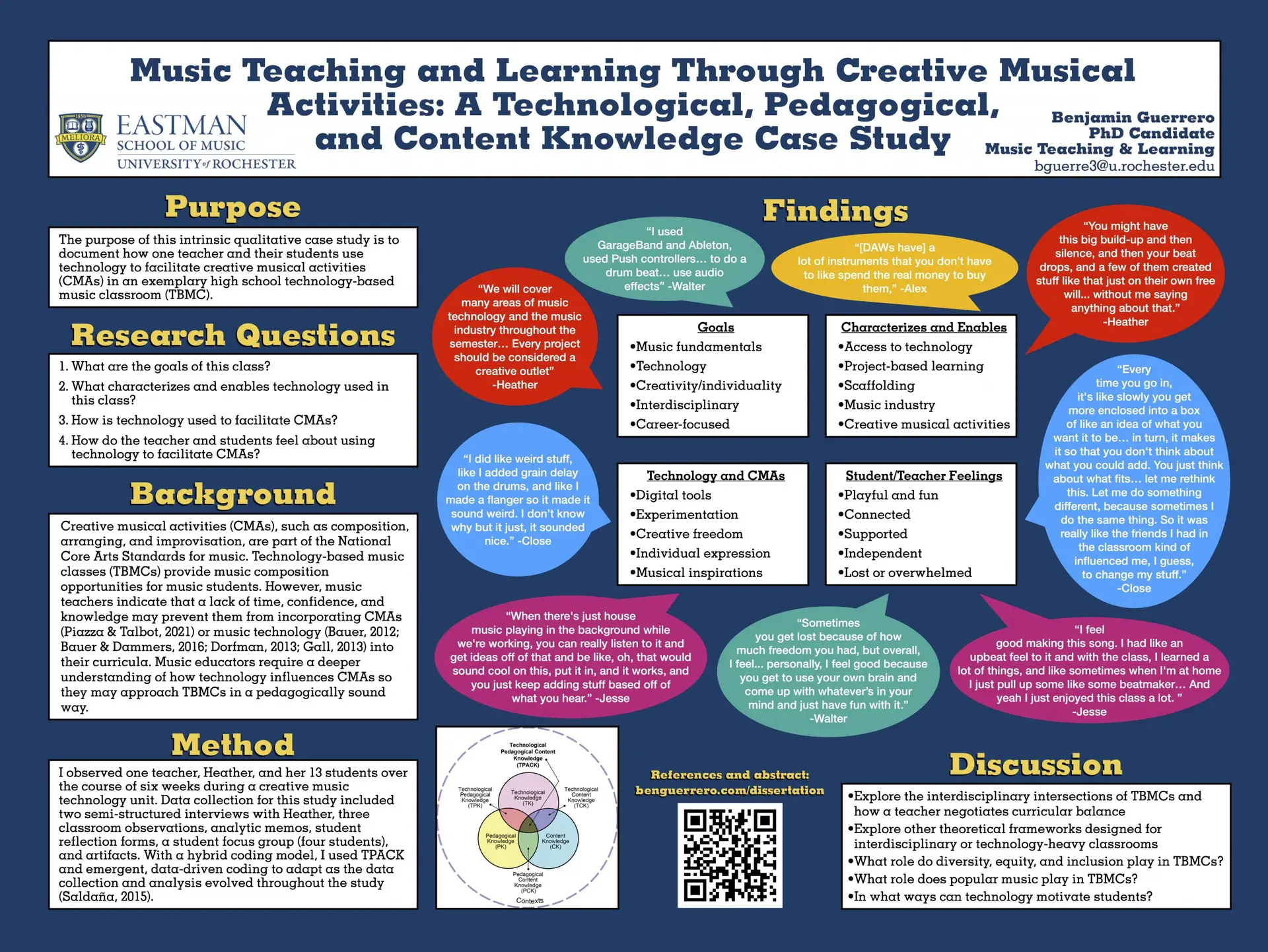

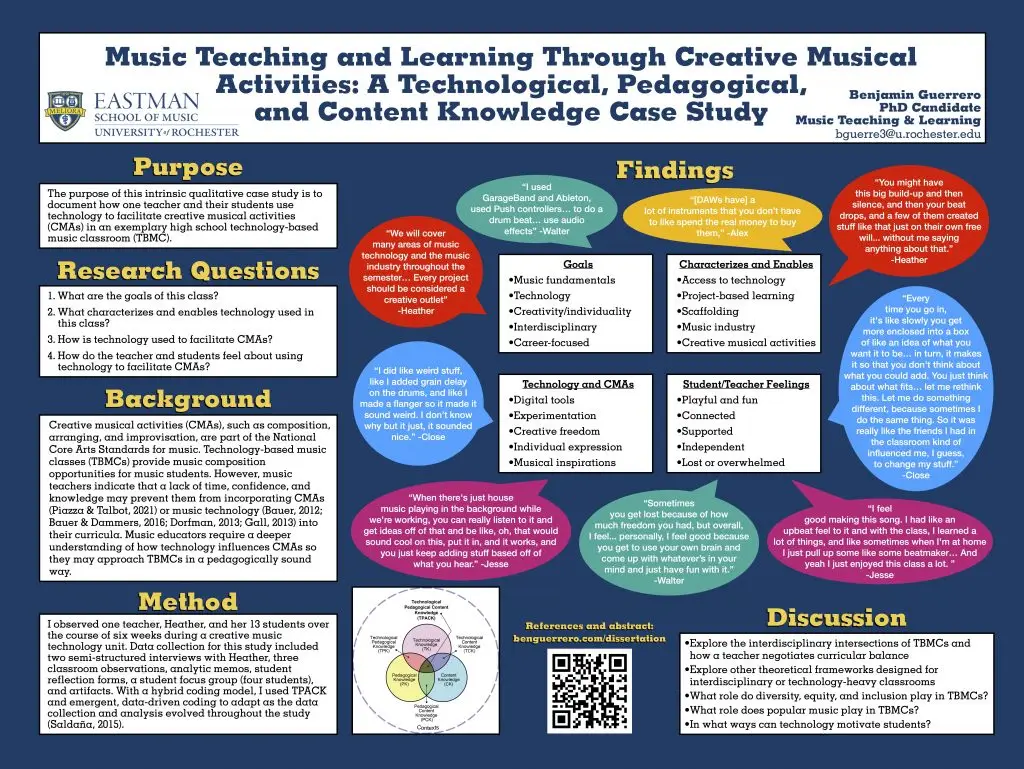

Music Teaching and Learning Through Creative Musical Activities: A Technological, Pedagogical, and Content Knowledge Case Study

Abstract

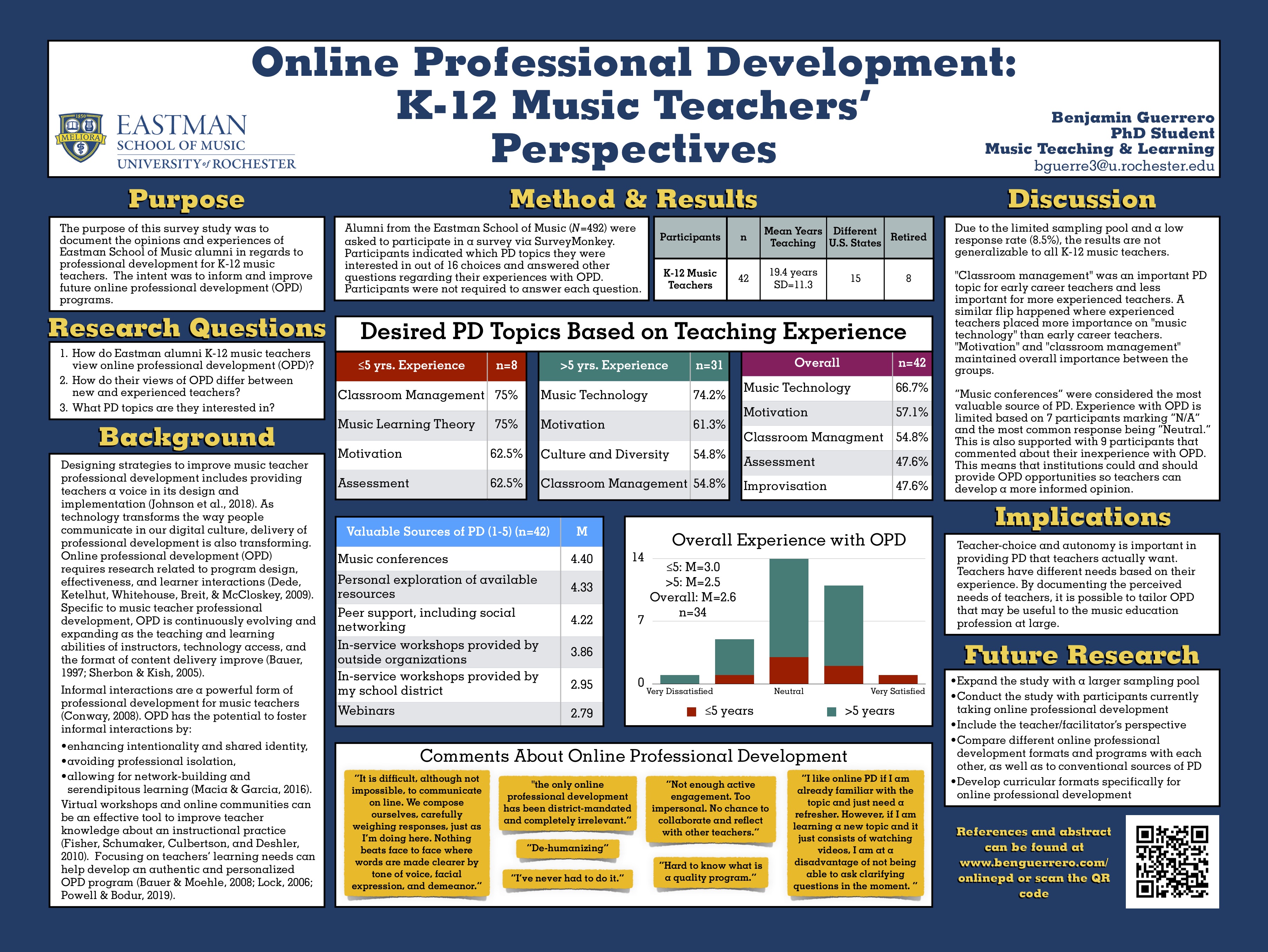

Use of technology in music teaching and learning has evolved rapidly in recent years. Creative musical activities (CMAs), such as composition, arranging, and improvisation, are part of the National Core Arts Standards for music. Technology-based music classes (TBMCs) provide music composition opportunities for music students. However, music teachers indicate that a lack of time, confidence, and knowledge may prevent them from incorporating CMAs (Piazza & Talbot, 2021) or music technology (Bauer, 2012; Bauer & Dammers, 2016; Dorfman, 2013; Gall, 2013) into their curricula. Music educators require a deeper understanding of how technology influences CMAs so they may approach TBMCs in a pedagogically sound way. The purpose of this intrinsic case study is to document how one teacher and their students use technology to facilitate CMAs in an exemplary high school TBMC. Research questions guiding this study include: 1) What are the goals of this class? 2) What characterizes and enables technology used in this class? 3) How is technology used to facilitate CMAs? and 4) How do the teacher and students feel about using technology to facilitate CMAs? Data collection included observations, analytic memos, semi-structured interviews, student reflections, student focus group(s), and classroom artifacts based on a 6-week creative music technology unit. After triangulating the data using a hybrid coding model, I present the emerging findings through the lens of the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge (TPACK) conceptual framework.

Keywords: music technology, creative musical activities, music education, technology-based music classes, TPACK

References

Abril, C. R. (2009). Responding to culture in the instrumental music programme: A teacher’s journey. Music Education Research, 11(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800802699176

Abril, C. R., & Gault, B. M. (2008). The state of music in secondary schools: The principal’s perspective. Journal of Research in Music Education, 56(1), 68–81.

Archambault, L. (2016). Exploring the use of qualitative methods to examine TPACK. In M. C. Herring, M. J. Koehler, & P. Mishra (Eds.), Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) for educators (pp. 65–86). Taylor & Francis Group.

Azzara, C. D. (2002). Improvisation. In R. Colwell & C. P. Richardson (Eds.), The new handbook of research on music teaching and learning (pp. 171–187). Oxford University Press.

Azzara, C. D., & Grunow, R. F. (2006). Developing musicianship through improvisation: Book 1. GIA Publications.

Azzara, C. D., & Snell, A. H. I. (2016). Assessment of improvisation in music. Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935321.013.103

Bakir, N. (2015). An exploration of contemporary realities of technology and teacher education: Lessons learned. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 31(3), 117–130.

Balkin, A. (1990). What is creativity? What is it not? Music Educator’s Journal, 76(9), 29–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3401074

Baser, D., Kopcha, T. J., & Ozden, M. Y. (2016). Developing a technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) assessment for preservice teachers learning to teach English as a foreign language. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(4), 749–764.

Bauer, W. I. (2010). Technological pedagogical and content knowledge for music teachers. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2010, San Diego, CA. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/34001

Bauer, W. I. (2012). The acquisition of musical technological pedagogical and content knowledge. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 22(2), 51–64.

Bauer, W. I. (2020). Music learning today: Digital pedagogy for creating, performing, and responding to music (2nd ed.). Oxford Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197503706.001.0001

Bauer, W. I., & Dammers, R. J. (2016). Technology in music teacher education: A national survey. Research Perspectives in Music Education, 18(1), 2–15.

Bauer, W. I., Hofer, M. J., & Harris, J. (2012). Grounded tech integration using K–12 music learning activity types. Learning & Leading with Technology, 40(3), 30–32.

Ben-Tal, O., & Salazar, D. (2014). Rethinking the musical ensemble: A model for collaborative learning in higher education music technology. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 7(3), 279–294.

Bernhard, H. C. I., & Stringham, D. A. (2016). A national survey of music education majors’ confidence in teaching improvisation. International Journal of Music Education, 34(4), 383–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415619069

Biasutti, M. (2015). Pedagogical applications of cognitive research on musical improvisation. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(614). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00614

Bolton, J. (2008). Technologically mediated composition learning: Josh’s story. British Journal for Music Education, 25(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051707007711

Burton, S. L., & Snell, A. H. I. (2018). Ready, set, improvise: The nuts and bolts of music improvisation. Oxford University Press.

Campbell, P. S., Myers, D., & Sarah, E. (2016). Transforming music study from its foundations: A manifesto for progressive change in the undergraduate preparation of music majors (Report of the Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major). College Music Society. https://www.music.org/pdf/pubs/tfumm/TFUMM.pdf

Chai, C. S., Koh, J. H. L., & Tsai, C.-C. (2013). A review of technological pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(2), 31–51.

Chai, C. S., Koh, J. H. L., & Tsai, C.-C. (2016). A review of the quantitative measures of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK). In M. C. Herring, M. J. Koehler, & P. Mishra (Eds.), Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) for educators (pp. 97–116).

Challis, B. (2009). Technology, accessibility and creativity in popular music education. Popular Music, 28(3), 425–431. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143009990158

Clark, W. H., Jr. (1986). Some thoughts on teaching creativity. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 20(4), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3332593

Clauhs, M., Franco, B., & Cremata, R. (2019). Mixing it up: Sound recording and music production in school music programs. Music Educators Journal, 106(1), 55–63.

Colvin, J. C., & Tomayko, M. C. (2015). Putting TPACK on the radar: A visual quantitative model for tracking growth of essential teacher knowledge. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 15(1), 68–84.

Crawford, R. (2009). Secondary school music education: A case study in adapting to ICT resource limitations. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 25(4), 471–488.

Cremata, R. (2010). The use of music technology across the curriculum in music education settings: Case studies of two universities [Doctoral dissertation, Boston University]. Boston, MA.

Cremata, R., & Powell, B. (2017). Online music collaboration project: Digitally mediated, deterritorialized music education. International Journal of Music Education, 35(2), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415620225

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Crow, B. (2006). Musical creativity and the new technology. Music Education Research, 8(1), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800600581659

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The systems model of creativity: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7

Culp, M. E., & Clauhs, M. (2020). Factors that affect participation in secondary school music: Reducing barriers and increasing access. Music Educators Journal, 106(4), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432120918293

Dacey, J. (2011). Historical conceptions of creativity. In M. A. Runco & S. R. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 608–616). Academic Press.

Dammers, R. J. (2007). Supporting comprehensive musicianship through laptop computer-based composing problems in a middle school band rehearsal [Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Dammers, R. J. (2009). A survey of technology-based music classes in New Jersey high schools. Contributions to Music Education, 36(2), 25–43.

Dammers, R. J. (2012). Technology-based music classes in high schools in the United States. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 194, 73–90.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. The Macmillan Company.

Dobson, E. (2012). An investigation of the processes of interdisciplinary creative collaboration: The case of music technology students working within the performing arts [Doctoral dissertation, Open University]. https://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/14689

Dobson, E. (2019). Talk for collaborative learning in computer-based music production. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 12(2), 141–164.

Dobson, E., & Littleton, K. (2016). Digital technologies and the mediation of undergraduate students’ collaborative music compositional practices. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(2), 330–350.

Dorfman, J. (2008). Technology in Ohio’s school music programs: An exploratory study. Contributions to Music Education, 35, 23–46.

Dorfman, J. (2013). Theory and practice of technology-based music instruction. Oxford University Press.

Dorfman, J. (2015). Perceived importance of technology skills and conceptual understandings for pre-service, early- and late-career music teachers. College Music Symposium, 55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26574400

Dorfman, J. (2016a). Exploring models of technology integration into music teacher preparation programs. Visions of Research in Music Education, 28.

Dorfman, J. (2016b). Music teachers’ experiences in one-to-one computing environments. Journal of Research in Music Education, 64(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429416649947

Elpus, K., & Abril, C. R. (2019). Who enrolls in high school music? A national profile of U.S. students, 2009–2013. Journal of Research in Music Education, 67(3), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429419862837

Emmons, S. E. (1998). Analysis of musical creativity in middle school students through composition using computer-assisted instruction: A multiple case study [Doctoral dissertation, Eastman School of Music]. Rochester, NY.

Escalante, S. I. (2019). Latinx students and secondary music education in the United States. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 37(3), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123318802335

Fairfield, S. M. (2010). Creative thinking in elementary general music: A survey of teachers’ perceptions and practices [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Iowa]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Ferreira, G. M. d. S. (2007). Crossing borders: Issues in music technology education. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 1(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.1.1.23/1

Freedman, B. (2013). Teaching music through composition: A curriculum using technology. Oxford University Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

Gall, M. (2013). Trainee teachers’ perceptions: Factors that constrain the use of music technology in teaching placements. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 6(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.6.1.5_1

Grasso, L. A., Parker, M., Graham, T. R., & Riley, J. P. (2019). Improvisation in band and orchestra: A review of literature. In D. A. Stringham & H. C. I. Bernhard (Eds.), Musicianship: Improvising in band and orchestra (pp. 3–21). GIA.

Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), 444–454.

Guilford, J. P. (1957). Creative abilities in the arts. Psychological Review, 64(2), 110.

Haning, M. (2016). Are they ready to teach with technology? An investigation of technology instruction in music teacher education programs. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 25(3), 78–90.

Harris, J., Grandgenett, N., & Hofer, M. J. (2010). Testing a TPACK-based technology integration assessment instrument. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, San Diego, CA.

Harris, J., Grandgenett, N., & Hofer, M. J. (2012). Testing an instrument using structured interviews to assess experienced teachers’ TPACK. In Research highlights in technology and teacher education 2012 (pp. 15–22). Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/bookchapters/8

Heines, J., Greher, G., Ruthmann, S., & Reilly, B. (2011). Two approaches to interdisciplinary computing + music courses. Computer, 44(12), 25–32.

Heller, G. N. (2011). From the melting pot to cultural pluralism: General music in a technological age, 1892–1992. Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, 33(1), 59–84.

Henry, W. (1996). Creative processes in children’s musical compositions: A review of the literature. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 15(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/875512339601500103

Hess, J. (2015). Decolonizing music education: Moving beyond tokenism. International Journal of Music Education, 33(3), 336–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415581283

Hickey, M. (2001). Creativity in the music classroom. Music Educators Journal, 88(1), 17–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/3399771

Hickey, M. (2012). Music outside the lines: Ideas for composing in K–12 music classrooms. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199826773.001.0001

Hickey, M., & Webster, P. R. (2001). Creative thinking in music. Music Educators Journal, 88(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/3399772

Hofer, M., Grandgenett, N., Harris, J., & Swan, K. (2011). Testing a TPACK-based technology integration observation instrument. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference.

Hofer, M., & Harris, J. (2010). Differentiating TPACK development: Using learning activity types with inservice and preservice teachers. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference.

Holt, M., & Jordan, J. (2008). The school choral program: Philosophy, planning, organizing, and teaching. GIA.

Hughes, J. (2005). The role of teacher knowledge and learning experiences in forming technology-integrated pedagogy. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13(2), 277–302. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/26105/

Jaipal-Jamani, K., & Figg, C. (2015). A case study of a TPACK-based approach to teacher professional development: Teaching science with blogs. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 15(2), 161–200.

Jassmann, A. E. (2004). The status of music technology in the K–12 curriculum of South Dakota public schools [EdD dissertation, University of South Dakota]. Vermillion, SD.

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1987). Reasoning, imagining, and creating. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 71–87.

Jones, C., & King, A. (2009). Peer learning in the music studio. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 2(1), 55–70.

Kaschub, M., & Smith, J. (2013). Composing our future: Preparing music educators to teach composition. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199832286.001.0001

Kerchner, J. L., & Strand, K. (2016). Musicianship: Composing in choir. GIA.

Kim, E. (2013). Music technology-mediated teaching and learning approach for music education: A case study from an elementary school in South Korea. International Journal of Music Education, 31(4), 413–427.

Kimmons, R., Graham, C. R., & West, R. E. (2020). The PICRAT model for technology integration in teacher preparation. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 20(1), 176–198.

Kimmons, R., & Hall, C. (2018). How useful are our models? Pre-service and practicing teacher evaluations of technology integration models. TechTrends, 62(1), 29–36.

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing TPCK. In Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) for educators (pp. 2–29). Routledge.

Kokkidou, M. (2013). Critical thinking and school music education: Literature review, research findings, and perspectives. Journal for Learning Through the Arts, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.21977/D9912644

Liu-Rosenbaum, A., & Creech, A. (2021). The role of technology in mediating collaborative learning in music. In Routledge international handbook of music psychology in education and the community (pp. 433–448). Routledge.

Martin, M. D. (1999). Band schools of the United States: A historical overview. Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, 21(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/153660069902100108

Martinez, S. L., & Stager, G. S. (2013). Invent to learn: Makers in the classroom. The Education Digest, 79(4), 11.

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being (2nd ed.). Van Nostrand.

McKnight, K., O’Malley, K., Ruzic, R., Horsley, M. K., Franey, J. J., & Bassett, K. (2016). Teaching in a digital age: How educators use technology to improve student learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 48(3), 194–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2016.1175856

McMullin, C. (2023). Transcription and qualitative methods: Implications for third sector research. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 34(1), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00400-3

Mellor, L. (2008). Creativity, originality, identity: Investigating computer-based composition in the secondary school. Music Education Research, 10(4), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800802547680

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Moon, K.-S., & Humphreys, J. T. (2010). The Manhattanville Music Curriculum Program: 1966–1970. Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, 31(2), 75–98.

Mroziak, J., & Bowman, J. (2016). Music TPACK in higher education. In M. C. Herring, M. J. Koehler, & P. Mishra (Eds.), Handbook of TPACK for educators (pp. 285–296). Taylor & Francis Group.

NASM. (2016). Philosophy. National Association of Schools of Music. https://nasm.arts-accredit.org/about/philosophy/

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Common core of data: America’s public schools. https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/

Nielsen, L. D. (2013). Developing musical creativity: Student and teacher perceptions of a high school music technology curriculum. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 31(2), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123312473610

Nilsson, B., & Folkestad, G. (2005). Children’s practice of computer-based composition. Music Education Research, 7(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800500042042

Oehrle, E. (1986). A method of evaluating the extent to which music education texts support creativity: An important aspect of contemporary music education. International Society for Music Education, 13, 169–178.

Piazza, E. S., & Talbot, B. C. (2021). Creative musical activities in undergraduate music education curricula. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 30(2), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083720948463

Pitts, A., & Kwami, R. M. (2002). Raising students’ performance in music composition through the use of information and communications technology (ICT): A survey of secondary schools in England. British Journal of Music Education, 19(1), 61–71.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. Vintage.

Powell, B. (2021). Modern band: A review of literature. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 39(3), 39–46.

Powell, B., & Burstein, S. (2016). Popular music and modern band principles. Routledge.

Powell, B., & Burstein, S. (2017). Popular music and modern band principles. In G. D. Smith, Z. Moir, M. Brennan, S. Rambarran, & P. Kirkman (Eds.), The Routledge research companion to popular music education (pp. 243–254). Routledge.

Puentedura, R. R. (2013). SAMR: Moving from enhancement to transformation. http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/000095.html

Randles, C. (2009). ‘That’s my piece, that’s my signature, and it means more’: Creative identity and the ensemble teacher/arranger. Research Studies in Music Education, 31(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103×09103631

Randles, C., & Stringham, D. (2013). Musicianship: Composing in band and orchestra. GIA.

Reese, S., & Rimington, J. (2000). Music technology in Illinois public schools. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 18(2), 27–32.

Rudolph, T. E. (1996). Teaching music with technology. GIA Publications.

Running, D. J. (2008). Creativity research in music education: A review (1980–2005). Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 27(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123308322280

Ruthmann, S. A. (2006). Negotiating learning and teaching in a music technology lab: Curricular, pedagogical, and ecological issues [Doctoral dissertation, Oakland University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Ruthmann, S. A. (2008). Whose agency matters? Negotiation pedagogical and creative intent during composing experiences. Research Studies in Music Education, 30(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103×08089889

Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Seddon, F. A., & O’Neill, S. A. (2001). An evaluation study of computer-based compositions by children with and without prior experience of formal instrumental music tuition. Psychology of Music, 29(1), 4–19.

Seddon, F. A., & O’Neill, S. A. (2003). Creative thinking processes in adolescent computer-based composition: An analysis of strategies adopted and the influence of instrumental music training. Music Education Research, 5(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461380032000085513

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

Siemon, D., Plaumann, R., Regenberg, A., Yuan, Y., Liu, Z., & Robra-Bissantz, S. (2016). Tinkering for creativity: An experiment to utilize Makey Makey invention kit as group priming to enhance collaborative creativity. AMCIS.

Snell, A. H., II. (2012). Creativity in instrumental music education: A survey of winds and percussion music teachers in New York State [Doctoral dissertation, University of Rochester]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education. (2014a). National core arts standards. http://www.nationalartsstandards.org

State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education. (2014b). National core arts standards — music technology strand. http://www.nationalartsstandards.org/sites/default/files/Music%20Tech%20Strand%20at%20a%20Glance%204-20-15.pdf

Stauffer, S. L. (2001). Composing with computers: Meg makes music. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 150, 1–20. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40319096

Stringham, D. A., & Bernhard, H. C. I. (2019). Musicianship: Improvising in band and orchestra. GIA.

Stringham, D. A., Thornton, L. C., & Shevock, D. J. (2015). Composition and improvisation in instrumental methods courses: Instrumental music teacher educators’ perspectives. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 205, 7–25. https://doi.org/10.5406/bulcouresmusedu.205.0007

Tai, S.-J. D., & Crawford, D. (2014). Conducting classroom observations to understand TPACK: Moving beyond self-reported data. Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2014, Jacksonville, FL. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/131189

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. (2012). Technological pedagogical content knowledge. tpack.org

TIM. (2009). Technology integration matrix. https://fcit.usf.edu/matrix/

Tobias, E. S. (2012). Composing, songwriting, and producing: Informing popular music pedagogy. Research Studies in Music Education, 35(2), 213–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X13487466

Tobias, E. S. (2013). Toward convergence: Adapting music education to contemporary society and participatory culture. Music Educators Journal, 99(4), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432113483318

Tobias, E. S. (2014). Flipping the misogynist script: Gender, agency, hip hop and music education. Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education, 13(2), 48–83.

Tobias, E. S., Campbell, M. R., & Greco, P. (2015). Bringing curriculum to life: Enacting project-based learning in music programs. Music Educators Journal, 102(2), 39–47.

U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics. (2010). Teachers’ use of educational technology in U.S. public schools: 2009, first look. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2010/2010040.pdf

U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Use of educational technology for instruction in public schools: 2019–20. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2021/2021017.pdf

Upitis, R., Abrami, P. C., & Boese, K. (2016). The use of digital tools by independent teachers. International Association for Development of the Information Society (IADIS) International Conference on Mobile Learning, Vilamoura, Algarve, Portugal.

Viig, T. G. (2015). Composition in music education: A literature review of 10 years of research articles published in music education journals.

Voogt, J., Fisser, P., Tondeur, J., & van Braak, J. (2016). Using theoretical perspectives in developing an understanding of TPACK. In Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) for educators (pp. 33–52). Routledge.

Vossoughi, S., & Bevan, B. (2014). Making and tinkering: A review of the literature. National Research Council Committee on Out of School Time STEM, 67, 1–55.

Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. Harcourt, Brace.

Ward, C. J. (2009). Musical exploration using ICT in the middle and secondary school classroom. International Journal of Music Education, 27(2), 154–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761409102323

Watson, S. (2011). Using technology to unlock musical creativity. Oxford University Press.

West, C., & Clauhs, M. (2015). Strengthening music programs while avoiding advocacy pitfalls. Arts Education Policy Review, 116(2), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2015.1007831

Williams, D. A. (2017). Music technology pedagogy and curricula. In S. A. Ruthmann & R. Mantie (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of technology and music education (pp. 633–646). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199372133.013.60

Williams, D. B. (2012). The non-traditional music student in secondary schools of the United States: Engaging non-participant students in creative music activities through technology. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 4(2–3), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.4.2-3.131_1

Wise, S. (2016). Secondary school teachers’ approaches to teaching composition using digital technology. British Journal of Music Education, 33(3), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051716000309

Wolff, C. (2000). Johann Sebastian Bach: The learned musician. W. W. Norton.